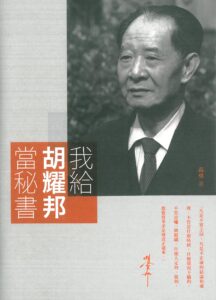

Gao Yong 高勇

Hong Kong: Joint Publishing Ltd 三聯書店(香港)有限公司, 2014

Reviewed by Bhim B. Subba (PhD Candidate, University of Delhi)

In the run-up to the centenary of the birth of Hu Yaobang, former General Secretary of the Communist Party of China and a disgraced successor of Deng Xiaoping, many biographies and stories of his life were published throughout China. Apart from two volumes by the People’s Daily in 2015, this memoir by Gao Yong, ‘To be a Secretary of Hu Yaobang’ (wo gei Hu Yaobang dang mishu), stands out in its narration of the leader’s personal and political life from the perspective of a close confidant, friend and secretary (mishu).

Hu Yaobang, a pioneer of reform, was an ‘organizational man’ with impressive credentials as an able revolutionary soldier, commander and political organizer. The author details how Hu was hand-picked by Chairman Mao to head the Chinese Communist Youth League (CYL) in 1952. Gao was appointed by the Organization Department to serve as Hu’s secretary from 1959 until 1964, and thus documented Hu Yaobang’s political journey within the party echelons. He characterized Hu as a masterful ‘strategist’ who teamed up with Deng to lead early reforms in post-Mao China. The piece rests on material documents like notes and letters, describing the author’s personal experience with a powerful leader who shaped China’s political and economic discourse in the reform era, including his death on April 15, 1989 which marked the beginning of the Tiananmen protests.

One of the most impressive accounts in the memoir is the author’s insightful detailing of Hu’s contribution to the rejuvenation of the CYL, and its rapid transformation until the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Instilling young minds with slogans such as “serving the people” and emphasizing correct education and knowledge were the primary goals. Hu was not only an ambitious politician, but also a voracious reader, hard worker, and loyal follower of Mao Zedong. However, this did not guarantee his escape from the Red Guard’s wrath, and for more than two years he was locked in a cowshed (niu peng) as an accused ‘renegade’ and ‘counter-revolutionary.’ Thanks to Deng, who was rehabilitated by 1973, Hu Yaobang was brought to head the party organization in the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in 1975. Under Hu’s leadership, the ills of the Cultural Revolution that shaped the state of economics and science in China were slowly undone. However, with his detractors like the Gang of Four (siren bang) still on the prowl, and factional politics at their zenith, his position was always threatened.

Though other official works on Hu Yaobang have been published in China, Gao’s memoir illuminates Hu’s personality and political acumen in surviving the competitive factional struggle in Chinese politics. Gao sheds light on the power struggle among different personalities that shaped the Chinese political landscape during the first two decades. Having served under such a personality, Gao’s experiences make this book a compelling read.

Many insightful memoirs, biographies and personal accounts of Communist Party leaders are published in Hong Kong and Taiwan with more relative ease than in Mainland China. However, in recent years, incidents involving harassment of writers and publishers in order to ‘sanitize’ and ‘gag’ publications, and even cases of individuals being ‘kidnapped’ and taken to the mainland for questioning, have been reported in the press. This can hinder scholars and China-watchers from understanding contemporary elite politics more objectively. The tolerance of the party-state is a big question for intellectuals, thinkers, and academics considering publishing material considered ‘sensitive’ for the party’s regime in the coming future.