Original images held by the Harvard-Yenching Library of the Harvard College Library, Harvard University

HOLLIS link to view all posters

Summary written by Juhee Kang (Ph.D., Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University)

Propaganda posters have long been a valuable primary source for scholars studying North Korea. Like other posters, they offer cultural and artistic narratives, but in this case, they further provide political and socioeconomic insights into a country largely sealed off from external observation. Their styles and themes often crystallize the most pressing issues at the time of their production. It is also conveniently evident that the North Korean central government, under the communist Korean Workers’ Party, is the driving force behind their production, with each embedded message functioning as a state directive aimed at civilians. These posters thus convey the regime’s priorities, its stances on key matters, and on some occasions, how it anticipates these messages might be received by the population. The Harvard-Yenching Library’s collection of North Korean posters presents an extraordinary window into contemporary North Korea. The collection, comprising over 500 fully digitized posters produced between 1997 and 2019, with a bulk from the late 2000s, showcases enduring elements of North Korean propaganda and new themes reflecting more recent historical developments and concerns.

In the Korean peninsula, propaganda posters stand as remnants of its division in 1950. After the end of Japanese colonization in 1945, Cold War politics split the peninsula along the 38th parallel, placing the South under U.S. and Allied occupation, while the North fell under Soviet influence. In 1948, when the promised period of occupation ended, neither the United States nor the Soviet Union allowed their respective Korean allies to unify the peninsula, resulting in the establishment of the Republic of Korea (South Korea) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea), each claiming sovereignty over the entire region. Erupted in 1950, the Korean War lasted three years and marked the first of many “hot” conflicts during the Cold War era.

In the aftermath of the devastating war, literacy rates on both sides of Korea were alarmingly low, at around 20%. Propaganda posters, with their intuitive visual messages, were mostly hand-painted and inexpensive to produce and became expedient tools for daily political communication. They appeared everywhere, not only in public spaces but also near private residences, local community sites, and workplaces. Their placements were strategic, ensuring constant visibility and reinforcing the intended message to be absorbed as a part of everyday life. Both North and South relied heavily on this medium for decades. In South Korea, however, compulsory elementary education raised the literacy rate to 95% by 1958, leading to a gradual reduction in the use of posters. By the 1990s, public messaging had largely shifted to televised and digital formats. In contrast, despite improved literacy rate, North Korea has continued to use propaganda posters for mass communication and political indoctrination likely due to limited material conditions.

The posters in the Yenching collection adhere to the tradition of socialist realism, retaining the main composition and color palette from their predecessors. First established in the 1930s, socialist realism demanded an idealized portrayal of life under socialism, depicting not life as it is but as it should be. As North Korean scholar Katharina Zellweger notes, this artistic style is designed to elicit specific, programmed responses from viewers. For instance, posters promoting agrarian production present idyllic, flawless scenes of farmland – familiar yet aspirational – and encourage viewers to internalize the realization of that image as a personal goal. Alternatively, posters that evoke a visceral response with exaggerated scenes of terror and violence, warn of imperialist – particularly American – aggression and reinforce messages of national self-defense ingrained since childhood. These scenes, occupying much of the poster’s physical space, are often aided by impactful, large-font taglines at the bottom.

The stylistic consistency, almost transhistorical in its uniformity, is a deliberate outcome of the Party government’s influence. Many of the posters, along with other state-supported artworks, are produced at centralized government art studios, facilities that reportedly employ around 1,000 of North Korea’s most talented artists. The Party directs these artists’ works, commissioning them and fostering a degree of internal competition within the studio over whose creations will be officially selected. A notable modern shift is that, unlike in the past, some individual artist information is now available in the Yenching Collection, marking a departure from the previous practice of treating artists as anonymous “art workers (yesul nodongja).”

There are also recognizable stylistic changes in the collection. In the past, propaganda posters have heavily relied on primary colors – red, blue, black, and yellow – each associated with carefully calibrated symbolic meanings: red represents socialism, aggression, and passion; blue stands for peace, harmony, and integrity, often seen in educational materials; black symbolizes darkness and evil, frequently used in anti-American and anti-South Korean posters; and gold or yellow denotes prosperity. However, in the Yenching collection, a more nuanced and modern use of colors is evident. While the primary colors still retain their meanings, the broader diversity of hues reflects contemporary design sensibilities, moving beyond the traditional palette and acknowledging material availability.

While these stylistic elements evoke the past and incorporate modern changes, the most significant takeaway from the Yenching Collection lies in the core themes of the posters. Familiar narratives are reiterated and reorganized, while new themes address more recent historical developments and concerns. There are also fresh interpretations of older themes, prompting scholars to question what drove these alterations. Enduring motifs include the idolization of the Kim family, calls for unification under North Korean leadership, and aggression toward the United States. Direct messaging to workers and encouragement of increased production are long-standing themes presented in new ways, while the emphasis on science and technology and a nostalgic yearning for the period between the 1950s and 1970s signal new directions.

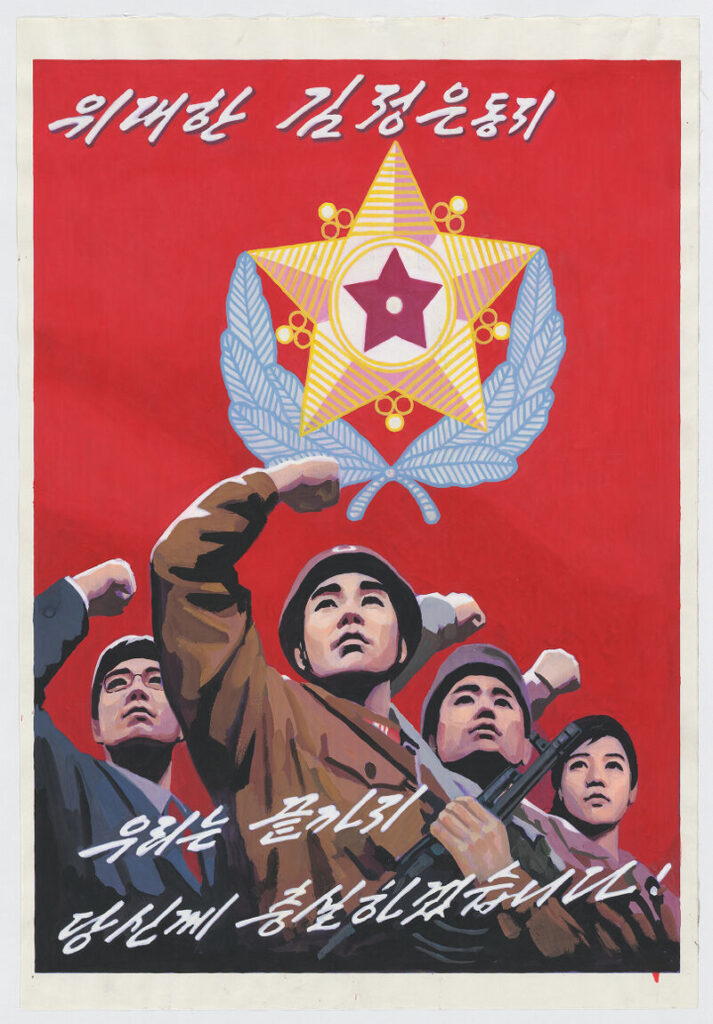

For example, in Figure 1, a classic communist red background frames a star representing the nation’s supreme commander – a position exclusively held by the Kim family. The poster bears the text, “The Great Compatriot Kim Jong Un,” at the top. Four figures, each symbolizing different sectors of North Korean “people workers (inmin)” – a blue-collar worker, a soldier, a laborer, and a woman in some kind of uniform – raise their fists in solidarity. The accompanying tagline reads, “We will forever be loyal to you!” This poster, likely produced after Kim Jong Il’s death in 2011, symbolizes Kim Jong Un’s rise to power and underscores the merging of the Party and ideology with the Kim family itself.

Figure 1: “The Great Compatriot, Kim Jong Un: We will forever be loyal to you!”

In Figure 2, again adhering to the classic socialist realist style, a yellow background highlights a central red space occupied by four figures – three men in Western work attire and a woman dressed in the traditional hanbok. They hold a flag that reads, “Self-determined unification.” The term “self-determined (jaju),” originating from the principle of self-determination in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, has been used in North Korea since 1945. While it originally referred to the right of nations to determine their own political fates, in North Korean propaganda, it has come to criticize South Korea’s alliance with the United States, insinuating that the U.S. is the force preventing unification. The smaller tagline, “All minjok shall unite the power to open the grand path toward self-determined unification!” reinforces this narrative. The term minjok, borrowed from the Japanese minzoku, refers to an ethno-racial group, a concept that became prominent in East Asia in the late 19th century, emphasizing shared historical and cultural identity. In the background, a faintly painted train likely represents the trans-Korean railway, a project that was discussed in 2000 during a period of diplomatic warmth under South Korean President Kim Dae Jung, who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. After its brief commencement in 2007, the train has never operated in full capacity.

Figure 2: “Self-determined Unification: The [Korean] Minjok shall unite the power to open the grand path toward self-determined unification!”

Revolving around the same theme, figure 4 adopts a much more colorful scheme to present North Korea’s perspective. The contrasting colorfulness suggests generates a sense of justified action. Here, a red arm representing North Korea holds a thumb over a nuclear launch button. The poster’s threatening tagline reads, “Should there be a war, the United States will not remain safe either!” The background features a map of the Pacific, with missile trajectories originating from the red Korean peninsula and aimed at key U.S. targets, possibly including San Francisco on the West Coast, Washington D.C. and New York on the East Coast, and Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. This imagery alludes to the North Korean fantasy of a united Korea under its leadership, projecting military strength against the United States.

Figure 3. “It is the United States that is the Axis of Evil.”

Figure 4. “Should there be a war, the United States will not remain safe either!”

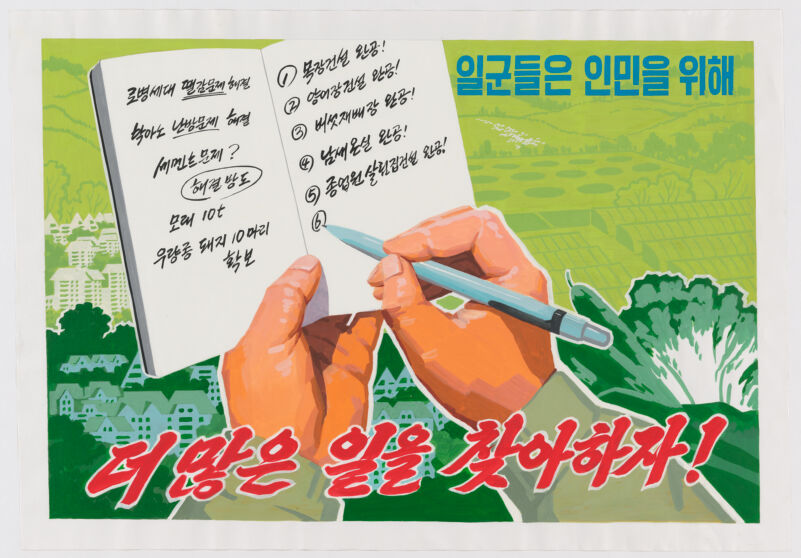

There are also older, thematically neutral directives aimed at workers, now presented in a modernized form. In Figure 5, the tagline encourages workers to take the initiative and proactively find additional tasks. The differentiation between “workers (ilgun)” and “people (inmin),” two groups likely overlapping in membership, is deliberate and serves to emphasize the workers’ authority and responsibility. As in most socialist regimes, the status of a worker carries pride, not through monetary or material compensation, but through a sense of duty. The worker depicted in the poster holds a notebook with a list of tasks: on the right page, “completion goals” for building fish and cow farms, a mushroom cultivation house, and a vegetable greenhouse, as well as finishing a housing project for service workers; on the left page, a list of “problems” to be resolved such as timber and cement shortages. These issues seem beyond any individual’s capability, but the poster implies that it is still every worker’s responsibility to push forward.

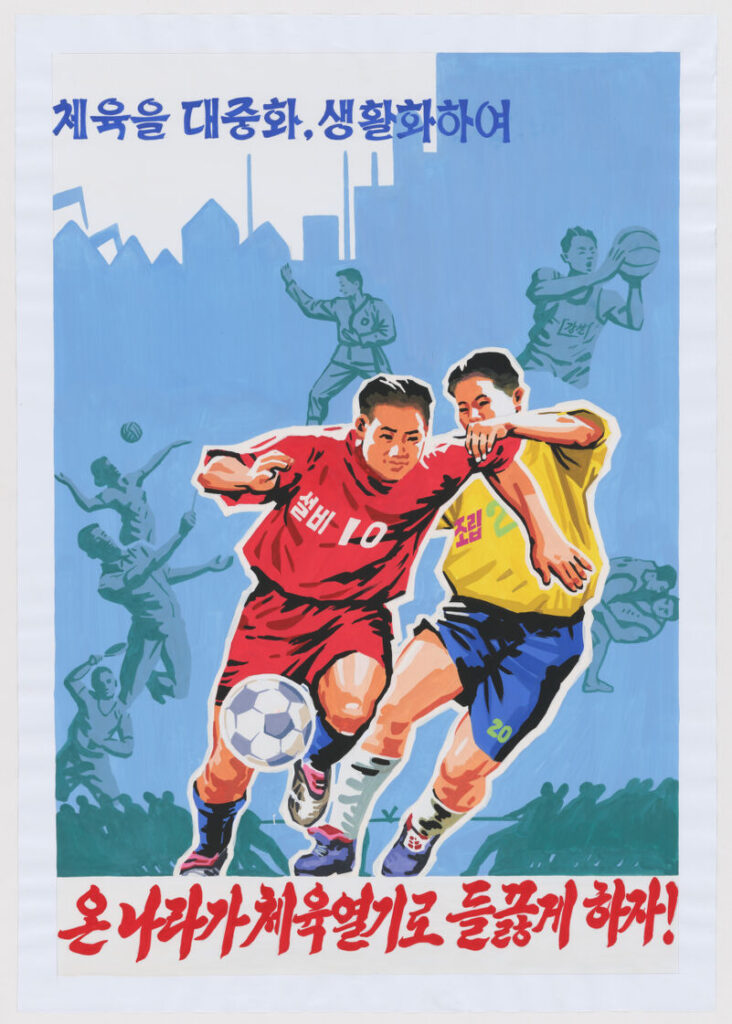

Figure 6 also reinterprets an older theme with a new design, focusing on the significance of physical and mental self-strengthening through sports. In the poster, two soccer players symbolize two key tasks within industrial production – “Plant/Equipment (seolbi)” and “Assembly (jolib).” These two tasks are depicted as competing forces vying for the ball, representing the drive and effort needed in industrial productivity. The entire nation is encouraged to engage in sports, as various athletic activities are shown in the background. The tagline reads, “Make sports ubiquitous and a part of everyday livelihood; let the whole country be fervent with sports passion!” Earlier propaganda emphasized physical preparedness through military training, but by the 2000s, this militaristic focus had shifted toward sports, which historically functioned as a form of surrogate warfare.

Figure 5. “Workers shall find more work for people!”

Figure 6. “Make sports ubiquitous and part of everyday livelihood: let the whole country be fervent with sports passion!”

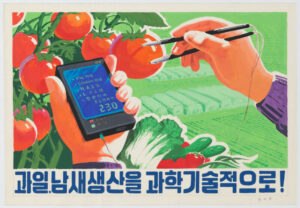

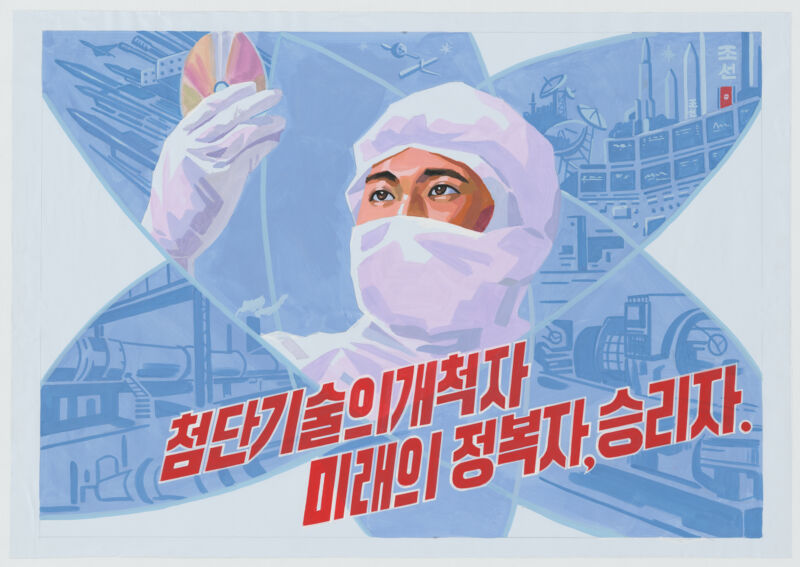

A prominent new theme shown in the collection is the strong emphasis on science and technology, which is integrated into nearly every aspect of production, from the arts to industry and agriculture. The posters depict both quantitative and qualitative improvements driven by technological advancements. Figure 7 illustrates the use of electronic machine to assess the quality of tomatoes, showcasing the role of technology in improving agricultural output. Meanwhile, Figure 8 underscores the importance of scientific innovation with the tagline, “The trailblazers of cutting-edge technology: the conquerors of the future, victors.” The poster features a gender-ambiguous scientist holding a computer disk, with a backdrop of various industrial and technological sites. The modern color scheme in both posters, which moves away from the traditional primary palette, conveys a more apolitical agendas and a sense of progress. Nonetheless, in Figure 8, the straightforward language suggests that North Korea’s worldview positions science and technology as the new battleground in the global race for dominance, with a clear winner and loser.

Figure 7. “Produce fruits vegetables scientifically!”

Figure 8. “The Trailblazers of the cutting-edge technology: the conqueror of future, victor”

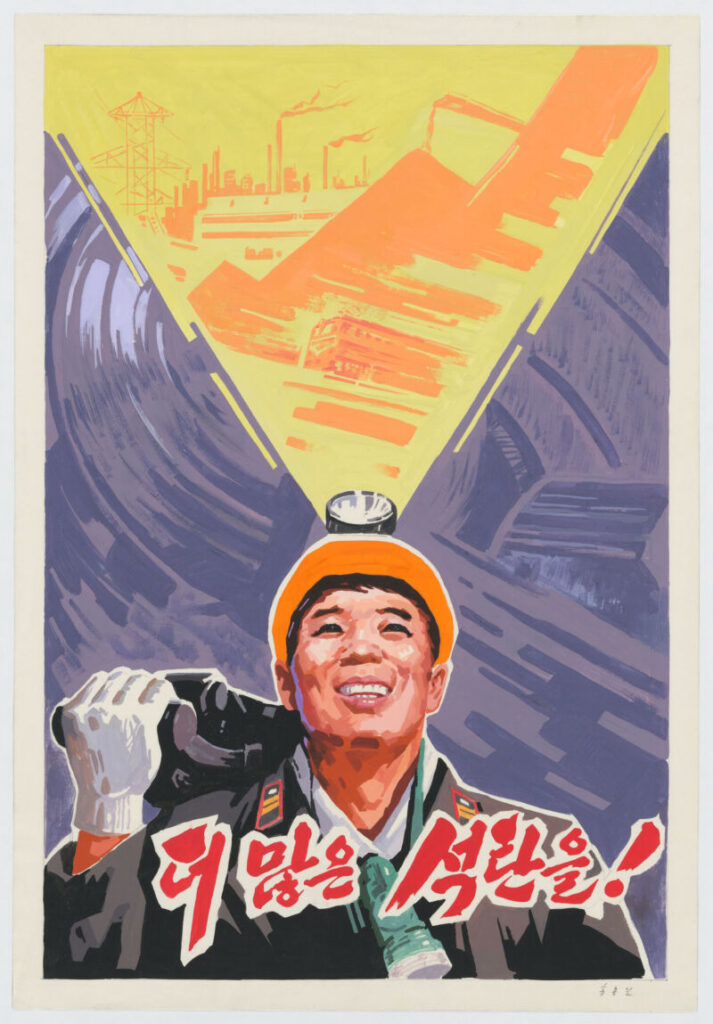

Another recurring theme presented in a modern context is the emphasis on self-reliance, particularly in the realm of energy. Figure 9, surprisingly a product of the 2000s, depicts a figure standing prominently and shouting for increased coal production, highlighting North Korea’s ongoing energy scarcity and limited technological capacity. This call for coal resonates with Figure 10, where a new entity – “Juche-metal (Juche cheol)” – is presented as the ultimate solution to the energy crisis. It’s unclear whether the poster is urging miners to produce more metals under the banner of “Juche” or if it is promoting a newly developed energy source called Juche-metal. Either way, the poster reinforces a strong “can-do” sentiment. The term “Juche” refers to the state ideology conceptualized by Kim Il Sung, which promotes self-reliance and autonomy, in contrast to the concept of “sadae,” which implies reliance on external powers. Juche remains a central principle of North Korean policy, especially in relation to energy production and technological development, as seen in the emphasis on generating new energy and materials under this guiding ideology.

Figure 9. “More coals!”

Figure 10. “Juche-metal, we can do it!”

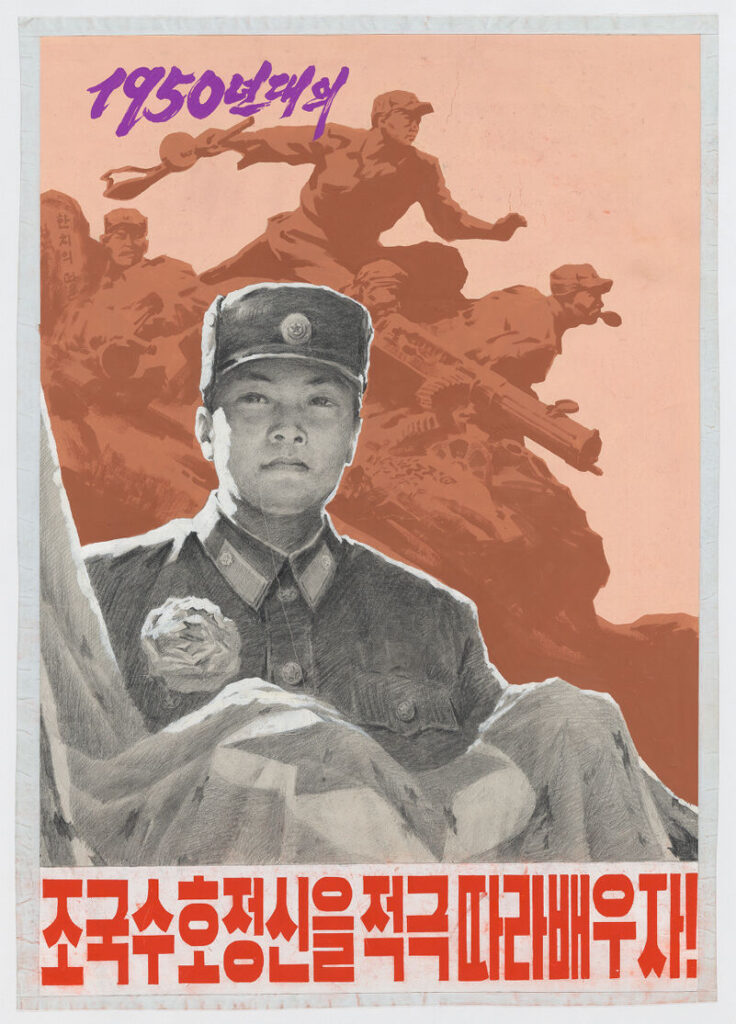

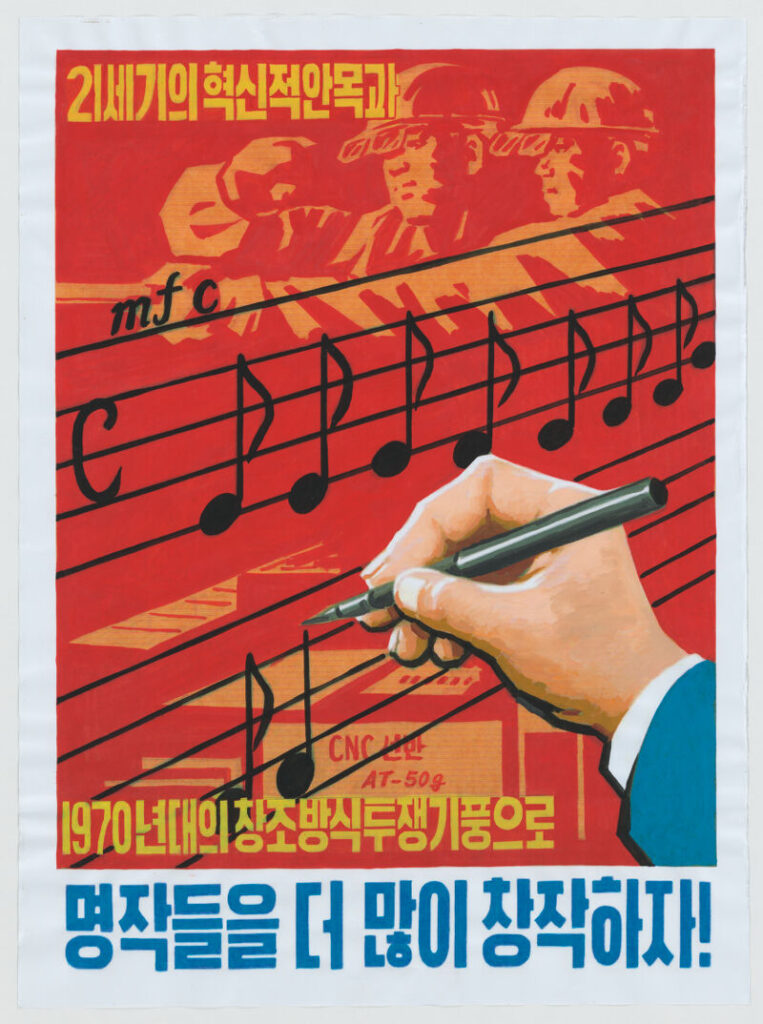

A particularly interesting new development in the collection is the nostalgia and yearning for the period between the 1950s and the 1970s. This was the only era when North Korea surpassed South Korea in nearly every metric of development. During this period, the country held greater influence in international politics and fostered a stronger sense of ideological loyalty among its people. It was also during this time that the mythology surrounding the Kim family began to take shape. It is curious to see a revival of this romanticization in the 2000s, especially when similar trends were observed in Chinese government propaganda around the same time.

Figure 11 carries the tagline, “One should admire and learn from the spirit of national self-defense from the 1950s,” urging a return to the values of that time. Similarly, Figure 12 promotes artistic production with the message, “Produce more masterpieces by blending the 21st century innovative perspective and the 1970s’ style of creative resistance,” suggesting that progress can be achieved by merging modern advancements with the resilience and creativity of past decades. This return to earlier ideals reflects an attempt to draw upon a period when North Korea was seen as stronger and more independent, possibly in response to challenges faced in the 2000s.

Figure 11. “One should admire and learn from the spirit of national self-defense from the 1950s!”

Figure 12. “Produce more masterpieces by blending the innovative perspective of the twenty-first century and the style of creative resistance from the 1970s!”

Likewise, the Yenching Collection’s fully digitized North Korean posters provide a remarkable window into the evolving priorities and concerns within the regime. From calls for self-reliance and technological advancement to a romanticized view of North Korea’s earlier successes, these posters reflect both continuity and change in the nation’s visual propaganda. Experts familiar with earlier posters can also discern which messages have faded or ceased to exist, offering another valuable avenue for analysis. For scholars interested in exploring the intersection of art, politics, and history in one of the world’s most closed-off societies, this collection offers a rare and invaluable resource, inviting further study into North Korea’s use of visual culture as a powerful tool for state messaging and control.