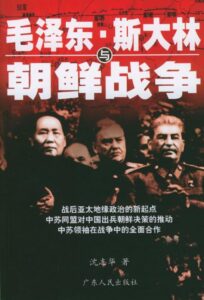

Shen Zhihua 沈志华

Guangzhou: Guangdong renmin chubanshe, 2013.2, third edition

Reviewed by Tian Wuxiong (PhD candidate, History, Peking University; HYI Archival Research Training Program Visiting Fellow)

Field: History

Key Words: the Korean War, Sino-Soviet Relationship, Mao Zedong, Stalin, Kim Il-sung

This is a new book, published just last year. But it is also an old book, whose first edition was published ten years ago and whose original draft was completed nearly twenty years ago. While the title and the structure of the chapters and sections remain identical to the 2003 edition, the content has changed substantially, beyond just adding newly accessible archival documents and providing more details. In the first edition, Shen Zhihua had already convincingly demonstrated that the launching of the Korean War was neither Stalin’s conspiracy nor a conspiracy among the three communist leaders. Shen’s vivid narration of historical process and the solid rigor of his explanations and interpretations of key issues, including Stalin’s motivations for allowing Kim Il-sung’s plan of reunification by force, as well as Mao Zedong’s decision to send troops to Korea, have not only won active response and recognition among the academic community, but have also turned this book into a bestseller, fundamentally reshaping Chinese public impressions and understandings of the Korean War. In spite of this, as leading cold war international historian Chen Jian commented, the third edition presents a “more comprehensive historical narrative” and is “full of new conclusions.”

According to Chen Jian, the book presents at least five fresh ideas with far-reaching significance. First, for Stalin to create and maintain an ice-free seaport in the Far East was a top priority when dealing with the Far East and formulating policies toward China and Korea. This is the logical starting point of Shen’s argument. Second, the new Sino-Soviet alliance treaty, by which Stalin finally gave up the Soviet sphere of influence in China (especially direct control over Port Arthur), brought the relationship between them to the brink of crisis. Stalin became extremely distrustful of Mao. It would have been crucial for Mao to regain Stalin’s trust if the Chinese Communist Party was to continue “leaning to one side”. Third, because of the loss of an ice-free port in the Pacific due to the newly signed treaty between China and the Soviet Union, Stalin changed his policy toward the Korean Peninsula and finally supported Kim Il-sung’s war plan to unify Korea. Fourth, Shen clearly lays out the reasons for China’s participation in the Korean War and the evolving considerations of Mao and other Chinese leaders in six different stages before sending troops to Korea. Ultimately, the Chinese decision was not only about the safety of its border, but also about keeping and strengthening “a reliable political posture of Sino-Soviet alliance, so as to fundamentally guarantee the stability and development of the new regime”. Fifth, it would have been possible for the Korean War and hot military confrontation between China and the U.S. to end in January 1951, three months after Chinese troops entered the war. Due to Mao’s serious miscalculation, China refused the mediation proposal in the United Nations Assembly and had to fight for another two years.

Meanwhile, nearly every aspect of this book’s conclusion will trigger controversies and raise doubts, as Chen Jian points out, though without explicitly singling out the contestable claims. As far as I know, one might doubt whether the priority of an ice-free port in Stalin’s Far East strategy really is enough to explain the origins of the Korean War. Launching a war would have been too risky and too costly, just for an ice-free port. Instead, why did Stalin and his successors not consider renting an ice-free port in North Korea during and after the war? Is there any evidence of any such initiative? As far as I know, the answer is no. And why did Stalin not ask Mao and Kim to end the war earlier in 1951 or 1952? Mao had proven his loyalty by sending troops to save North Korea, and the huge cost of the war had become a great burden for the Soviet Union. If Stalin’s objective had been to gain access to an ice-free port, it would have been better to end the war in 1951 or 1952 and then seek to rent a seaport from North Korea. I believe that the motivations for Stalin’s support for Kim’s plan must be complicated and multi-layered, just as Mao’s changing considerations in different stages before sending troops to Korea. From Shen’s elaborate description and wise and inspiring analysis in chapter four, one gets a sense that Mao was not going to war for any single factor alone: Neither for border safety; nor for commitments to the socialist bloc and the international communist movement; nor for revolutionary passion; and also not for politically posturing in the Sino-Soviet alliance. In fact, all of these four factors weighed into Mao’s consideration, and Mao’s emphases changed depending on internal and external circumstances. So was Stalin’s.

Undoubtedly, the third edition will not be the last word on the subject matter. Shen himself might be the one further revising the book in the future, as he has done with previous editions. Nevertheless, readers will benefit from picking up this book. It not only provides facts and conclusions, but the book and its author represent the tireless pursuit of historical truth.