As a scholar of international relations, Chu Duy Ly’s interest in the world beyond his home country of Vietnam began well before he entered university. “In the past I collected postage stamps – I learned more about the world around me through those stamps. And of course, I grew up with Japanese comics, Chinese classical literature, Soviet novels, American cartoons, and world music!” This interest in the global stage around Vietnam led him to study international relations for his BA and MA in Vietnam, before entering the doctoral program at the National University of Singapore in 2017, where he is a HYI-NUS Joint Doctoral Scholar. He describes his path to academia as initially somewhat reluctant: “I started to work for an entertainment company since my third year as an undergraduate. I didn’t think I could become a scholar – my style was very different from colleagues, I had long hair, looked like a rebel, and listened to rock and metal.” He was persuaded to stay and work as a TA, which is when he met a visiting professor who later became his MA supervisor. “I felt I had some similarities with him. [He taught me that] when you become a lecturer, the main thing is to transfer knowledge to your students; not your appearance. He gave me the inspiration to become a professor.”

As a scholar of international relations, Chu Duy Ly’s interest in the world beyond his home country of Vietnam began well before he entered university. “In the past I collected postage stamps – I learned more about the world around me through those stamps. And of course, I grew up with Japanese comics, Chinese classical literature, Soviet novels, American cartoons, and world music!” This interest in the global stage around Vietnam led him to study international relations for his BA and MA in Vietnam, before entering the doctoral program at the National University of Singapore in 2017, where he is a HYI-NUS Joint Doctoral Scholar. He describes his path to academia as initially somewhat reluctant: “I started to work for an entertainment company since my third year as an undergraduate. I didn’t think I could become a scholar – my style was very different from colleagues, I had long hair, looked like a rebel, and listened to rock and metal.” He was persuaded to stay and work as a TA, which is when he met a visiting professor who later became his MA supervisor. “I felt I had some similarities with him. [He taught me that] when you become a lecturer, the main thing is to transfer knowledge to your students; not your appearance. He gave me the inspiration to become a professor.”

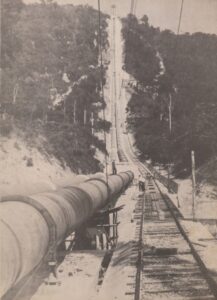

For his doctoral dissertation, Ly looks at hydropower dams and nation-building in postcolonial Asia, taking Da Nhim Hydroelectric Power Dam in South Vietnam as a case study and comparing it with similar projects elsewhere in Asia. Ly grew up in the central highlands of Vietnam, in the same region as the Da Nhim Dam, which was constructed in the early 1960s using a Japanese war reparations fund. Although growing up he was generally aware of the dam, it wasn’t until he began his doctoral studies that he learned the interesting stories behind it. “The Da Nhim hydroelectric power project was constructed by the Japanese with war reparations and a loan from the Import-Export Bank of Japan. Yutaka Kubota (久保田豊), President of Nippon Kōei (Nippon Kōei Kabushiki Kaisha 日本工営株式会社), the company that designed and supervised the dam, worked in Korea in the colonial time and constructed several large-scale hydropower dams and industrial projects there.” Ly finds this connection intriguing: “I’m trying to argue that he’s bringing his vast experience of developing comprehensive development projects from the colonial time and transferring it to the post-colonial time. Instead of seeing a rupture between the two periods, I’m trying to trace the similarities and continuities between the post-colonial large-scale technical projects in Asia and those done in the colonial times.”

For his doctoral dissertation, Ly looks at hydropower dams and nation-building in postcolonial Asia, taking Da Nhim Hydroelectric Power Dam in South Vietnam as a case study and comparing it with similar projects elsewhere in Asia. Ly grew up in the central highlands of Vietnam, in the same region as the Da Nhim Dam, which was constructed in the early 1960s using a Japanese war reparations fund. Although growing up he was generally aware of the dam, it wasn’t until he began his doctoral studies that he learned the interesting stories behind it. “The Da Nhim hydroelectric power project was constructed by the Japanese with war reparations and a loan from the Import-Export Bank of Japan. Yutaka Kubota (久保田豊), President of Nippon Kōei (Nippon Kōei Kabushiki Kaisha 日本工営株式会社), the company that designed and supervised the dam, worked in Korea in the colonial time and constructed several large-scale hydropower dams and industrial projects there.” Ly finds this connection intriguing: “I’m trying to argue that he’s bringing his vast experience of developing comprehensive development projects from the colonial time and transferring it to the post-colonial time. Instead of seeing a rupture between the two periods, I’m trying to trace the similarities and continuities between the post-colonial large-scale technical projects in Asia and those done in the colonial times.”

Yutaka Kubota

Ly’s research looks at “an alternative, transnational network of ideals, materials, capitals, technologies, and peoples connecting Japan, the United States, and Southeast Asia.” The idea of comprehensive development (Sōgō Kaihatsu総合開発) by creating multipurpose dams (dams not just for electricity, but for irrigation, navigation, flood control, and creating industrialized zones) had its root in state-led development projects during the 1930s such as the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in the US and the Five Year Plans in the USSR. “Engineers from Japan came to the US to learn about them, as they were members of the World Power Conference (now World Energy Conference) and its sub-commission, the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD), and brought the ideas back to Japan, where they were merged with Japanese leaders’ visions of comprehensive development of land and rivers in order to construct East Asia (Tōakensetsu東亜建設), both at home and abroad. After Japan invaded East Asian countries, they created large-scale technical systems such as hydroelectric dams and railways in Manchuria, Korea, and Taiwan.” Returning to Japan after defeat in World War II, the engineers later tried to “use the experience and ideas of ‘comprehensive development’ from colonial times and sell them to the newly independent countries. The inter-Asia connections to hydropower dams are a knowledge of constructing large-scale technical systems. The dam project is not just material, but the idea of knowledge.”

The Da Nhim dam was constructed in the 1960s, during the Cold War. Ly notes the “unique position of Japan, as both a recipient and sender[of aid]. They received technical aid and loans from the United States and the World Bank for reconstruction and development long after the US Occupation ended in 1952, and they transferred that to developing countries. What were the relations between Japan, the US, and South Vietnam?” The US government didn’t financially and technically support the Da Nhim hydropower dam project in South Vietnam, instead sponsoring an “Atomic Power” (Nguyên Tử Lực) project and thermal power plants. This gave an opening for the Japanese to step in, with the support of the South Vietnamese government for the dam project. Ly is interested in how these decisions unfolded: “If we approach from a traditional Cold War studies perspective, we think that because Japan and South Vietnam were US allies, they would follow the modernization and nation building ideas of ‘big brother’ which emerged as a part of American Cold War policies, but my thesis actually proves another point –some decisions were made in South Vietnam, not by the Americans or the Japanese. The South Vietnamese politicians and engineers decided what they were going to do. I’m trying to bring in that history, shifting focus from the US and USSR to the smaller nations. It is also needed to mention that some decisions were concluded in Japan, not by the Americans.”

The Da Nhim dam was constructed in the 1960s, during the Cold War. Ly notes the “unique position of Japan, as both a recipient and sender[of aid]. They received technical aid and loans from the United States and the World Bank for reconstruction and development long after the US Occupation ended in 1952, and they transferred that to developing countries. What were the relations between Japan, the US, and South Vietnam?” The US government didn’t financially and technically support the Da Nhim hydropower dam project in South Vietnam, instead sponsoring an “Atomic Power” (Nguyên Tử Lực) project and thermal power plants. This gave an opening for the Japanese to step in, with the support of the South Vietnamese government for the dam project. Ly is interested in how these decisions unfolded: “If we approach from a traditional Cold War studies perspective, we think that because Japan and South Vietnam were US allies, they would follow the modernization and nation building ideas of ‘big brother’ which emerged as a part of American Cold War policies, but my thesis actually proves another point –some decisions were made in South Vietnam, not by the Americans or the Japanese. The South Vietnamese politicians and engineers decided what they were going to do. I’m trying to bring in that history, shifting focus from the US and USSR to the smaller nations. It is also needed to mention that some decisions were concluded in Japan, not by the Americans.”

To conduct his research, Ly relies on Vietnamese, Japanese, and French documents in the national archives in Vietnam and Japan. “I’m lucky to be stuck in Vietnam! Every day I go to the National Archives II in Saigon.” He describes how in 2011 the government issued a law allowing scholars to read top secret and secret documents from the Republic of Vietnam. “This is a very good chance for scholars to approach those primary data. I get a lot of data from the letters and the reports which Vietnamese and Japanese officials and engineers sent to each other.” He also uses memoirs of the Japanese engineers who worked on the hydropower dams: “They constructed the projects, they remember the time and what the challenges and opportunities were, and what they saw as the role of the Japanese in doing those projects (even if it was somewhat naïve).” Although there are not similar memoirs written by those on the Vietnamese side of the project, Ly has been able to talk with a few engineers, now in their 80s and 90s, who worked on the dam project. “I contacted to a former professor of Grenoble Polytechnique University and Energy Economics Institute, now living in France, who belonged to the office of the president, which was in charge of supervising the contract and gave recommendations to the president on the project. I learned a lot from him. I also talked to another engineer who worked in both governments (before and after the unification of Vietnam) – he still has documents when he was selected to go to Japan for a hydropower dam training program for Vietnamese engineers.”

To conduct his research, Ly relies on Vietnamese, Japanese, and French documents in the national archives in Vietnam and Japan. “I’m lucky to be stuck in Vietnam! Every day I go to the National Archives II in Saigon.” He describes how in 2011 the government issued a law allowing scholars to read top secret and secret documents from the Republic of Vietnam. “This is a very good chance for scholars to approach those primary data. I get a lot of data from the letters and the reports which Vietnamese and Japanese officials and engineers sent to each other.” He also uses memoirs of the Japanese engineers who worked on the hydropower dams: “They constructed the projects, they remember the time and what the challenges and opportunities were, and what they saw as the role of the Japanese in doing those projects (even if it was somewhat naïve).” Although there are not similar memoirs written by those on the Vietnamese side of the project, Ly has been able to talk with a few engineers, now in their 80s and 90s, who worked on the dam project. “I contacted to a former professor of Grenoble Polytechnique University and Energy Economics Institute, now living in France, who belonged to the office of the president, which was in charge of supervising the contract and gave recommendations to the president on the project. I learned a lot from him. I also talked to another engineer who worked in both governments (before and after the unification of Vietnam) – he still has documents when he was selected to go to Japan for a hydropower dam training program for Vietnamese engineers.”

Now half-way into his HYI fellowship, Ly has found a tremendous benefit from participating remotely in classes and workshops. “I’m really happy that I have had a chance to work with top notch professors and audit a few classes.” He finds that being part of HYI’s community is “a great chance to know many scholars from different areas and different countries. Attending the workshops with HYI scholars has also given me some ideas about future research. I’d like to explore how different groups of Vietnamese have actually thought about science and technology throughout history, and different visions of science and technology that go beyond intellectual history to describe how it shaped certain political, social or cultural outcomes.”

Related Stories

Announcements

HYI Scholar Eiko Kawamura awarded Prize in Classical Japanese Literary ScholarshipMonday, November 4, 2024