Kinoshita Naoyuki 木下直之

Tokyo: Shinchō-sha, 2012

Reviewed by Sadamura Koto (PhD Candidate, the University of Tokyo; HYI Visiting Fellow, 2013-14)

Keywords: Japan, History of Art, Visual Culture, Cultural Studies

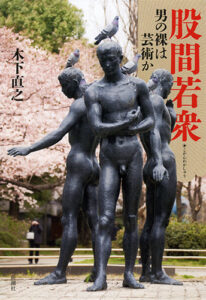

Those who have some knowledge of classical Japanese literature might have raised an eyebrow at the title Kokan wakashū, which makes a pun on Kokin wakashū 古今和歌集, the famous anthology of poems from the tenth century. Instead of the word kokin 古今 which signifies “ancient and modern,” Kinoshita shocks the reader with an unexpected choice of word, kokan 股間 which indicates “crotch.” The following word wakashū is the same in sound as 和歌集 “anthology of Japanese poetry” but here it means 若衆 “young men.” I went along with the playfulness of the Japanese title and have come up with this English title, Brothers of the Groin; however, I have to note that this is entirely my improvisation and that this is not an official translation of the title. As the amusing tone of the title suggests, Kinoshita’s investigation into representations of the male nude in Japanese art is delivered in this book with touches of humor.

The main focus of the book is sculpture of the male nude standing in a public space in Japan. The inquiry started when Kinoshita noticed the obscure and highly unnatural representation of the genitalia of these male figures. The book shows his consistent attitude in his academic inquiry in which he pays attention to and carefully scoops up dissonance that his subject testifies in its assigned environment. (This time, it was a pair of male figures standing naked in front of a train station.) He then investigates how such things come into being, locating them in their historical contexts by reading into materials he has thoroughly gathered. Such an approach and method have characterized Kinoshita’s research since his early monumental work Bijutsu to iu misemono: Abura-e chaya no jidai 『美術という見世物 油絵茶屋の時代』 (Art as a Spectacle: The Age of Oil Painting Teahouses. Tokyo: Heibon-sha, 1993).

In Bijutsu to iu misemono, Kinoshita dealt with a transitional period of late nineteenth century (from late Edo period to early Meiji era) and the process of re-organization and re-definition of the visual culture in Japan which took place in accordance with the newly introduced idea of “art” originated in Europe. He paid particular attention to what was dropped off from the category “art” in this process of modernization. One of the examples he took up in the book was iki-ningyō (living dolls) which makes an appearance also in Kokan wakashū. The contrast between an extremely realistic depiction of a male iki-ningyō’s genitals and the awkwardly deformed representation of the groin of a modern male nude sculpture is visually striking. Kinoshita looks at the conceptual changes regarding “art” in the Meiji era (1868-1912) which led to such ambiguous expression of male genitalia. Then, he follows the struggle of artists, from the Meiji era to the post-war period, who had to justify their works as “art” both visually and conceptually.

In search of representations of male bodies in other forms, Kinoshita looks at nude photography and photographs whose theme is the body, such as those of dancers and of people with tattoos, as well as rather rare examples of painted works. The book questions the obscure position of the male nude, when in contrast there has always been a strong insistence on the female nude as art. So many examples can be found that are based on or play with the premise that the female body is or can be art. What, then, about the male body? Whether it would be considered as art or obscenity has certainly been a more perilous question for the male nude representation.

Kinoshita’s strength lies in the new and unexpected materials he discovers as he walks around Japan and beyond. “Brothers of the groin” from all over Japan are assembled in the book, and together, they start crying out for an explanation of their existence. Kinoshita’s research into historical materials – articles in journals and magazines, photographic records, and teaching materials at art schools – reconstructs the context of the time. This prepares the grounds for an understanding of the origins of these sculptures and reveals the long struggle in art of the Meiji and post-Meiji eras hidden under the obscure expression of the male crotch. The topic might seem eccentric at the first glance but the book cuts into fundamental questions of what has constituted “art” in the modern times.

This study of the male nude is Kinoshita’s on-going project and has been proving its potential to relate to other interesting topics such as a comparison with their counterparts in Europe, the representation of genitalia in Japanese visual culture including shunga (erotic pictures) and its reception in the modern era. (“Kaettekita kokan wakashū” (Return of the Brothers of the Groin) in Geijutsu shinchō, No.63 (11), Tokyo: Shinchō-sha, November 2012, 88-101. Presentations: “The Fig Leaf That Fluttered in from Europe: The Male Nude in Japanese Art” at School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 19 June 2013; “Shunga versus ‘The Nude’ in Modern Japan” at the British Museum, 5 October 2013.) With Kokan wakashū, the reader will be introduced to this new and fertile ground for inquiry. It provides a fresh perspective on various problems that had arisen in the course of the modernization of art in Japan and their persistent influence up to the present.