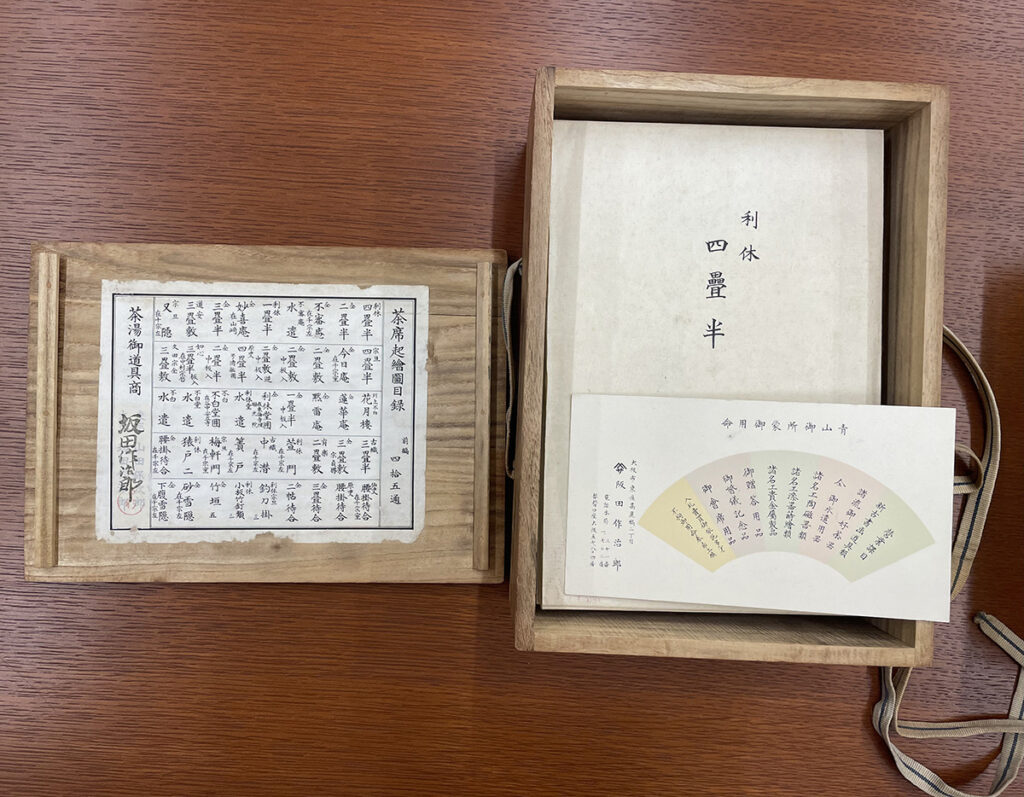

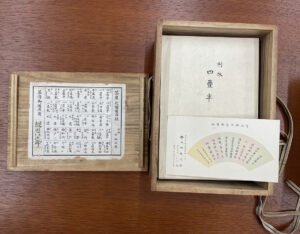

[奈良] : 坂田作次郎, [190-] [Nara?] : Sakata Sakujirō, [190-]; 90 folded leaves of plates in 2 cases : all illustrations ; 27 cm

Original images held by the Harvard-Yenching Library of the Harvard College Library, Harvard University

Summary written by Juhee Kang (Ph.D. Candidate, Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University)

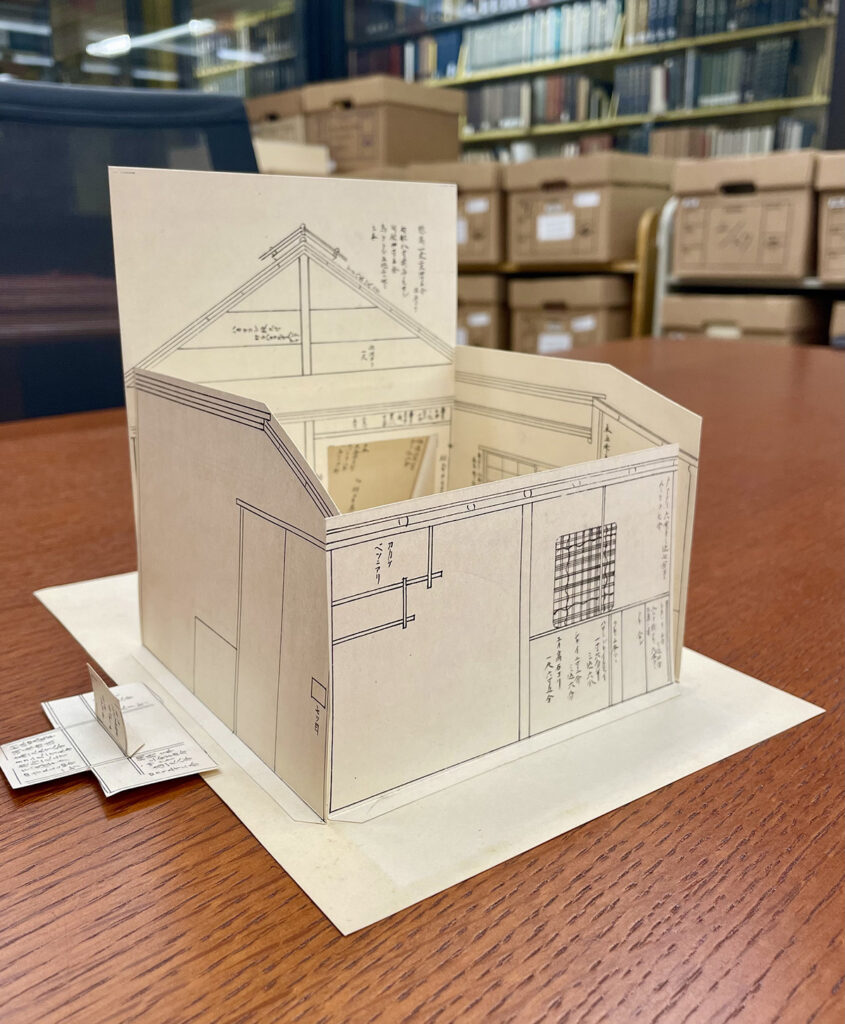

Chaseki Okoshiezu Mokuroku consists of two boxes full of individually wrapped pop-up architectural models (90 models in total). Each model functions as a miniature, representing the physical space of a tea ceremony house (chashitsu 茶室) famous at the turn of the twentieth century in Japan. By erecting the flaps of the pop-up model, one can reconstruct the teahouse in its three-dimensional form, complete with interior details and notes explaining their functions and construction materials.

Scholars of architecture, arts, religion, and history (among others) will find great value. The first decades of the twentieth-century, when Chaseki Okoshiezu Mokuroku was likely published, the tea ceremony was both a marker of cultural heritage and a fashionable practice among Japan’s new consumer society. Purportedly originated in the late 12th century with the introduction of tea by Buddhist monks returning from China, the Japanese tea ceremony had evolved into a religious practice around the sixteenth century. The ceremony acquired its ideals of simplicity, harmony, and spirituality which emerged from the Zen Buddhist emphasis on the meditative and communal experience centered around tea preparation and consumption. Then, from the late 19th century, as Japan underwent rapid modernization, it emerged as a cultural counterbalance, symbolizing traditional values and aesthetics. Simultaneously, with the rise of consumer culture, it became increasingly commodified. Tea utensils, once handmade and ceremonial, were mass-produced and sold in growing urban markets. Once exclusive, tea schools also expanded their reach, offering lessons to the burgeoning middle class eager to embrace and display cultural refinement amidst the modern industrial landscape. We may speculate that given the lavishness of its packaging, Chaseki Okoshiezu Mokuroku was part of a commercial venture targeting potential consumers with wealth.

Scholars of architecture, arts, religion, and history (among others) will find great value. The first decades of the twentieth-century, when Chaseki Okoshiezu Mokuroku was likely published, the tea ceremony was both a marker of cultural heritage and a fashionable practice among Japan’s new consumer society. Purportedly originated in the late 12th century with the introduction of tea by Buddhist monks returning from China, the Japanese tea ceremony had evolved into a religious practice around the sixteenth century. The ceremony acquired its ideals of simplicity, harmony, and spirituality which emerged from the Zen Buddhist emphasis on the meditative and communal experience centered around tea preparation and consumption. Then, from the late 19th century, as Japan underwent rapid modernization, it emerged as a cultural counterbalance, symbolizing traditional values and aesthetics. Simultaneously, with the rise of consumer culture, it became increasingly commodified. Tea utensils, once handmade and ceremonial, were mass-produced and sold in growing urban markets. Once exclusive, tea schools also expanded their reach, offering lessons to the burgeoning middle class eager to embrace and display cultural refinement amidst the modern industrial landscape. We may speculate that given the lavishness of its packaging, Chaseki Okoshiezu Mokuroku was part of a commercial venture targeting potential consumers with wealth.

Even beyond its value as a primary source, Chaseki Okoshiezu Mokuroku enables scholars to imagine the spatial experience that a participant of the tea ceremony would have had. Living in posterity, we rarely have access to the physicality of historical experiences, which not only enhances our understanding of the ceremony but also explains how the space – and all its components, such as the different skewedness of the ceiling, the airflow, and the play of light on designated spots – would have affected one’s perception of the ritualistic power the tea ceremony held.