Original images held by the Harvard-Yenching Library of the Harvard College Library, Harvard University

Summary written by Trevor Menders (Ph.D. Candidate, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard University)

Those who would hold power in Japan’s Tokugawa Shogunate (1615 – 1868) recognized the imminent threat of colonization posed by the growing presence of European missionaries and traders in the decades leading up to their ascendance. As such, once in place, the military regime banned both denizens’ egress and foreigners’ ingress for the duration of its rule, making exceptions for only a handful of Chinese and Korean delegations as well as Dutch traders. Nonetheless, the world beyond the archipelago captured the period Japanese imagination, leading to the circulation of print books that featured illustrated accounts of peoples from as far off as India and Brazil. Japanese Reports on Foreigners at once continues with and radically departs from this bibliographic legacy as a compendium of illustrated missives about new sets of foreigners to arrive in Japan in 1853, namely those of American commodore Matthew Perry (1794 – 1858) into Edo Bay on July 8th and Russian admiral Yevfimiy Putyatin (1803 – 1883) to Nagasaki’s harbor on August 12th.

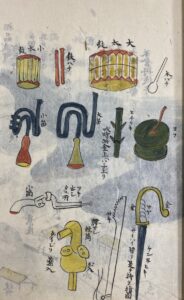

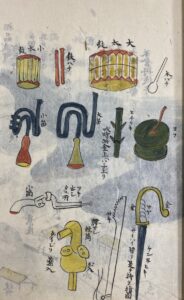

Instead of the deftly designed and woodblock-printed lofty tales of earlier books, Japanese Reports comprises a range of firsthand accounts describing a huge, even disjointed variety of details from these foreigners’ incursions, all written and drawn by hand. The first section of the book provides approximate sketches of a variety of American accoutrements, including fantastical iterations of musical instruments like trumpets and drums alongside more recognizable depictions of ammunition bags, guns, holsters, and swords (figures 1 and 2). The labels of these instruments reflect the accounts’ hearsay nature: two horn-like instruments labeled kobue 小笛and ōbue大笛, “little flute” and “big flute,” indicate the strictly eyewitness nature of these accounts and how little cultural knowledge was exchanged in these initial interactions.

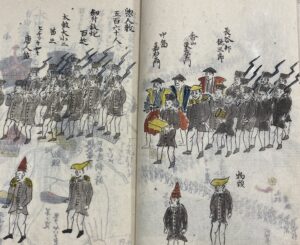

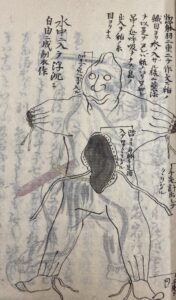

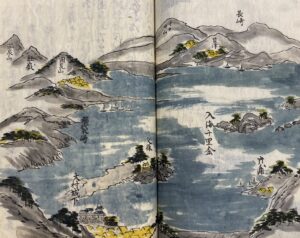

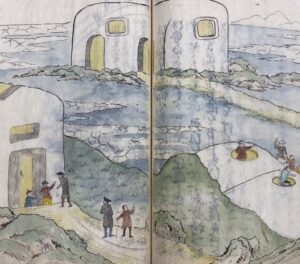

The following portions of the book provide views of the events surrounding Perry’s negotiations of trade agreements with detailed labels for the places, events, and people involved (figures 3 and 4); a taxonomy of the types of hats worn by the American forces and their presumed constituent material; a short treatise and illustration of an American diving suit (figure 5); and textual accounts of the negotiations between the two sides, before giving way to a detailed map of where Yevfimiy’s forces landed at Nagasaki (figure 6) accompanied by detailed, fantastical illustrations of how Russian society might appear (figure 7) as well as reports on the earliest Russian-Japanese negotiations, and more. Similar documents are found in the collections of Brown and Yale Universities as well as the Library of Congress and the Tokyo Metropolitan Library, but this volume contains portions seemingly not included elsewhere, making it all the more enlightening for this turbulent period of modern Japanese international relations.

Figure 1: The first page of the Japanese Reports on Foreigners, comprising uncolored sketches of fantastical musical instruments and an ammunition bag.

Figure 2: An excerpt from the first section of the Reports, comprising colored sketches of more fantastical musical instruments, another ammunition bag, utensils, blades, and other indeterminate foreign objects.

Figure 3: A birds-eye view of the temporary structures where Perry negotiated with Japanese representatives.

Figure 4: A view of the procession of Perry’s forces to the negotiation area, accompanied by Japanese chaperones.

Figure 5: First of a two-page illustrated treatise on diving suit technology used by Perry’s forces.

Figure 6: Illustration of the Nagasaki area harbor where Yevfimiy landed.

Figure 7: Illustration of Russian society based off oral accounts circulating at the time.