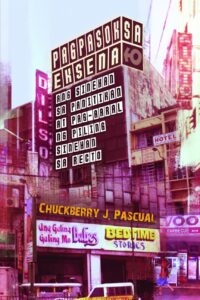

Chuckberry J. Pascual

Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2016

Reviewed by Christian Go, National University of Singapore

Chuckberry J. Pascual’s Pagpasok sa Eksena: Ang sinehan sa panitikan at pag-aaral ng piling sinehan sa Recto (2016) (Entering the Scene: The Movie Theater in Philippine Literature and a Study of Selected Movie Theaters in Recto) investigates standalone theaters in the Philippines as spaces for expressions of homosexual desire. The book explores the different ways these theaters are transformed within gay imaginary and through material practices. It presents a compelling account of liminal spaces that are fraught with tensions and touches on issues of sexuality, sex work, inequality, and space.

The book is divided into 5 chapters. Chapter 1 outlines the book’s theoretical foundations and methodology. The chapter utilizes Butler (1999) and Lefebvre (1991) to conceptualize a performative approach to space and describes an eclectic methodology that combines a close reading of Philippine literary texts and ethnographic work done by the author from 2007 to 2008. Chapter 2 sketches the history of standalone theaters in the Philippines. In this chapter, Pascual notes that standalone theaters emerged locally during the American colonial period (1898-1946) and became a popular establishment in the 70s and 80s, but eventually declined in popularity in the succeeding decades due to the rise of malls and mall culture. In the same chapter, Pascual establishes the history of movie houses as sexualized spaces and notes that the space has been tied to prostitution (dating back to 1862) and homosexual activity, particularly during the 1980s. Chapter 3 presents a close reading of excerpts of select literary texts (i.e., poetry, fiction, drama) from Filipino gay authors to map the topography of theaters as homosexual spaces. As Lefebvrian representations of space, Pascual notes that literary texts employ tropes of dirt and darkness to render theaters as liminal and contentious spaces that have not been sanitized by heteronormative norms. In Chapter 4, Pascual presents a vivid account of the material and semiotic construction of four theaters (i.e., Ginto, Dilson, Hollywood, and Roben) and the practices that take place within these establishments. The final chapter presents a summary and the author’s concluding thoughts.

The book presents a fascinating analysis of Philippine standalone movie theaters as homosexual spaces. By approaching the homosexualization of these establishments through an innovative combination of literary and sociocultural analysis, the author conveys a range of understandings of the space. The use of literary texts as a form of ethnography provides an interesting entry point in understanding the queer and possibly liberating potential of the movie theater such that it is within the confines of this space where norms are suspended, blurred, and remade. It is noteworthy that the author also adopts a cautious stance on such representations and avoids an uncritical analysis of these works and juxtaposes these representations with careful consideration of the theater’s material and corporeal facets. Pascual thoughtfully reiterates in the conclusion that there are limitations to a recuperative reading of movie theaters, as the material conditions of gay patrons and male prostitutes still render them marginalized within broader heterosexual society. Chapter 4, which is the highlight of the book, provides vignettes of the visceral and living dimensions of the theater space. For instance, Pascual engages the sensorium of the theater and posits the ways in which its appearance, smell, and sound correspond to the covert knowledge of individuals that visit and inhabit the space. At the same time, individuals who share this knowledge find themselves in unequal power relations that are mediated by sexuality, desirability, and the commodification of bodies. A noteworthy section of Chapter 4 was the analysis of graffiti written in the toilets at Dilson, which is one of the standalone movie theaters discussed in the book. The graffiti writer, presumably a male prostitute, expresses disgust against his clientele and wishes that the theater gets bombed. The strong negative affects expressed by the prostitute encapsulate the complex nature of the movie theater as a gay space where heterosexism and homophobia are decentered but not completely subverted. Scholars of literature, geography, cultural studies, queer studies, and anthropology may find Pagpasok sa Eksena useful to further understand the role of space in the shaping of sexual identities and practices in the Philippines.