Original images held by the Harvard-Yenching Library of the Harvard College Library, Harvard University

Summary written by Saranya Choochotkaew (Assistant Professor in Japanese Studies, Chulalongkorn University; HYI Visiting Scholar, 2024-25) and Jingyi Yuan (AM student, Regional Studies – East Asia, Harvard University)

A slideshow of the images is included at the bottom of the page.

What is your favorite pastime for celebrating the advent of the New Year? If you were living in nineteenth-century Japan, you might have enjoyed a board game named e-sugoroku 絵双六 (picture sugoroku), a racing game similar to Snakes and Ladders.[1] The e-sugoroku board is a flat sheet of paper full of illustrated small squares. Each player places their game piece at the square labelled “start” (furidashi 振り出し) and progress towards the “goal” (agari 上がり) square based on the throw of the dice.

In this article, we will introduce Harvard-Yenching Library’s diverse collection of sugoroku boards and envelopes published from the late Edo period to the end of the World War II. These games, with themes ranging from Buddhist cosmology, moral lessons for women, and war-time propaganda, offer us a fascinating glimpse into censorships and dynamics of the publishing industry as well as the religious, social, and political environments of the time.[2]

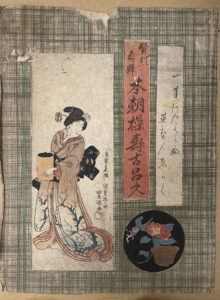

Among the library’s recent acquisitions of late-Edo and Meiji book covers (TJ 6289 7175) are two sugoroku envelopes from the late 1840s, featuring didactic tales for women while incorporating auspicious designs for the New Year. Both designs depict combinations of two or more of the following motifs: plum blossoms, camellias, handball (temari 手毬) and shuttlecock paddles (hagoita 羽子板). Besides, both designs replace the standard characters for the game, 双六 (lit. “double sixes”), with the characters 壽古呂久 or 壽吾六, emphasizing longevity and good fortune.

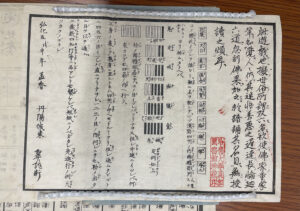

Image 1

One envelope, titled “Virtuous and Faithful Women of This Realm sugoroku” (Kenretsu teifu honchō misao sugoroku 賢烈貞婦本朝操寿古呂久, Image 1), is published by Izumiya Ichibei 和泉屋市兵衛 during the Kōka 弘化era (1844-1848). The envelope is illustrated by Utagawa Kunisada 歌川国貞 (Toyokuni II 二代豊国, 1786–1864), while designer of the corresponding game board is Keisai Eisen 渓斎英泉 (1791-1848).[3] The “start” square depicts a group reading scene featuring four women and a girl seated in a circle. Each subsequent square highlights exemplary Japanese women from historical and legendary tales, such as Ono no Komachi 小野小町and Tomoe Gozen巴御前, likely the subjects of the stories being read.

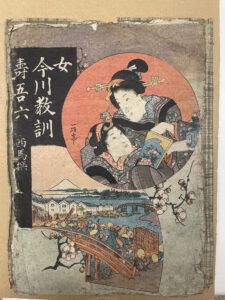

Image 2

The other envelope (Image 2), titled “Precepts for Women sugoroku” (Onna imagawa kyōkun sugoroku 女今川教訓双六), bears a name reminiscent of ōraimono 往来物 (elementary textbooks). Illustrated by Utagawa Kuniteru I 初代歌川国輝 (active c. 1818-1860) and published by Sanoya Kihei 佐野屋喜兵衛in 1849, the game board depicts behaviors women were admonished to avoid at the time, such as “gossiping by a well” (idobata 井戸端) and “being unfilial” (fukō 不孝).[4] One square even features the admonishment “staying in bed after waking up (while letting your husband do the chores)” (asane 朝寝).

Although presented as a didactic tool, the game’s underlying logic appears satirical. The “goal” is described as “the (ideal) Way of being husband and wife” (fūfu no michi 夫婦の道), where the husband should be treated as superior and the wife being obedient. However, the preceding squares leading to this goal include behaviors such as “being indulgent” (kyōsha 驕奢), “looking down upon a horse-dung collector” (bafun tori 馬糞取), and “being close to Buddhist priests” (butsusan 仏参). Moreover, the content of the game is attributed to Rakutei Saiba 楽亭西馬 (1799-1858), a well-known gesaku (“playful literature”) author.

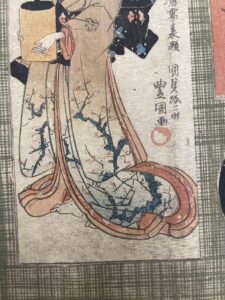

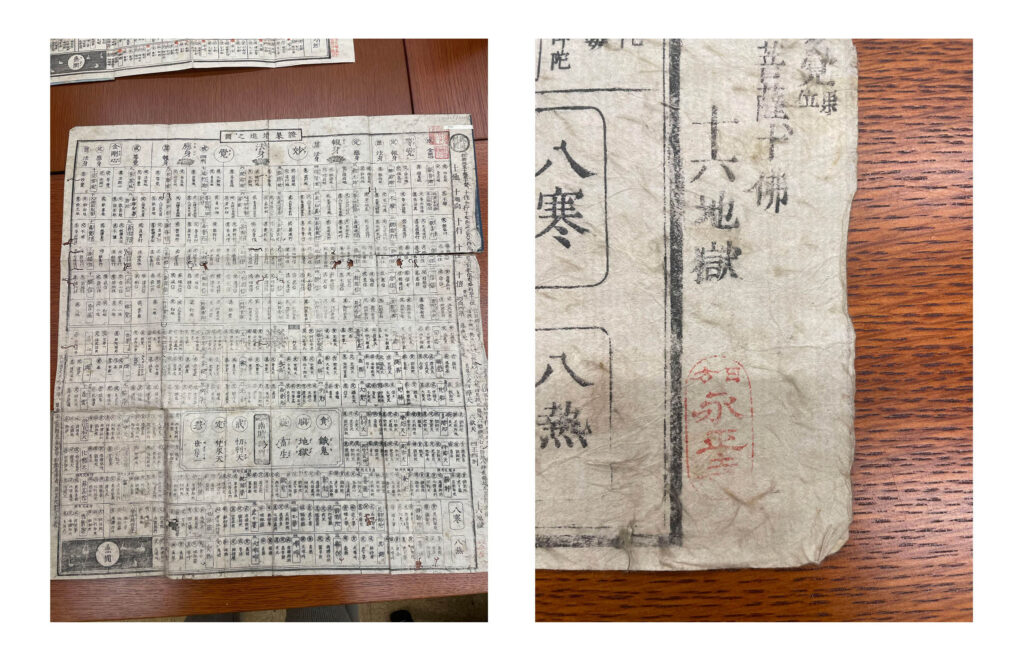

Image 3

Both sugogroku envelopes provide insight into the limitations placed on commercial publishing during the Tenpō 天保 era (1830-1844). In 1842, legislation was enacted to ban woodblock prints that depicted the extravagant and vibrant images of Kabuki actors and courtesans. By focusing on moral tales and historical themes, the designers of these sugoroku board games could still portray beautiful women within acceptable boundaries. Furthermore, the envelope of Kenretsu teifu honchō misao sugoroku 賢烈貞婦本朝操寿古呂久demonstrates a clever approach to creating a luxurious aesthetic without risking violation of government restrictions. Its modest checkered background (kōshi-mon 格子紋) contrasts with the textured backdrop behind the female figure, which evokes the refined texture of danshi 檀紙, producing a pop-up effect (Image 3).

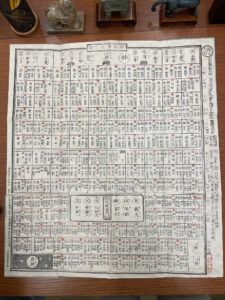

Image 4

Three sugoroku boards in the HYL collection feature religious themes. Two of these are titled “Diagram of Advancement of Enlightenment” (Shōka zōshin no zu 証果増進之図), often referred to as “Buddha Dharma sugoroku” (buppo sugoroku 仏法双六) or “[Buddhist] Descriptive Titles sugoroku” (meimoku sugoroku 名目双六). These boards illustrate Buddhist cosmology and the path from Jambudvīpa (Nanenbushū 南閻浮州) to the attainment of the dharmakāya (hosshin 法身). Of the two copies, the 1848 version published by Suiryūken 翠龍軒 in Tanʼyō 丹陽 (in present-day Niwa, Aichi Prefecture) is in a better condition and includes a manual (Image 4) attached to the back.

Interestingly, although the game is believed to one of the oldest types of e-sugoroku,[5] the manual notes that the game is an adaptation of other secular versions of sugoroku:

“The game imitates the sugoroku widely known among secular players, repurposing it to teach young disciples at temples about Enlightenment. Depending on their degree of bewilderment and the swiftness of karmic retribution, some are stuck in the long cycles of reincarnation within the six paths, while others obtain enlightenment quickly. In addition, [while playing,] the disciples recite the names of each square, thus sparing their masters the trouble of teaching them how to read.”

Image 5

As indicated by this manual, all terms inscribed on the game board include furigana to aid pronunciation (Image 5). The board is further annotated with red ink, including a red dot above the name of each square. In some cases, these dots highlight a printed number, which indicates the position of a square within a series of locations, as annotated along the right side of the game board. For example, the numbering reveals that the “Realm of Non-Perception” (musō 無想) is the thirteenth of the eighteen realms in the “Form Realms” (shikikai色界).

Moreover, although the patterns produced by throwing six colored sticks are encoded with symbolic meanings—the three disciplines (kai 戒, jō 定, and e 慧) and the three poisons (ton 貪, jin 瞋, and chi 癡)—the red annotations simply number them from one to six. This numbering system may have provided players with a convenient shortcut for determining their next move.[6]

The other “Buddha Dharma sugoroku” board in the HYL collection (Image 6) contains fewer furigana and shows signs of wear, including moth-eaten holes. It bears the seal of Nippō Eishōji 日方永正寺 in present-day Wakayama (Image 7), which indicates that the board was once owned by the temple, likely serving as an educational tool for young disciples.

Image 6 and Image 7

Image 8

Another Buddhist-themed sugoroku is titled “Land of Immeasurable Life Pure Land sugoroku” (Muryōjukoku-jōdo-sugoroku 無量寿国浄土双六, Image 8), where the goal is to achieve “superior grade superior form [of rebirth in Amida’s Pure Land]” (jōbonjōshō 上品上生).[7] Its highly pictorial design, the use of hiragana rather than kanji, and the inclusion of money marks (Image 9) all suggest that this board was intended for laypeople and may have been used for gambling purposes.

Interestingly, unlike the aforementioned “Buddha Dharma sugoroku” that show many creases and are folded and stored in book cases, the “Pure Land sugoroku” is mounted as a hanging scroll. It comes from a collection of Buddhist-themed hanging scroll by Bruno Petzold (1873-1949), a minister of the Tendai sect. Why would such a monochrome game board be mounted as a hanging scroll? We propose that this may be due to its visual resemblance to the Taima Mandala. It is likely that during Petzold’s time in Japan (1910–1949), the board had lost its original function as a game and had been repurposed as a ritual implement or reinterpreted as a piece of “Buddhist art” tailored to appeal to Western collectors.[8]

Image 9

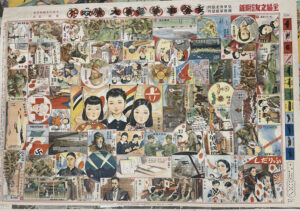

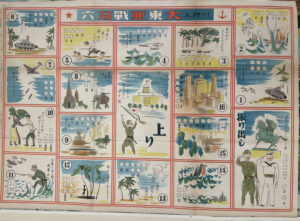

Beyond the premodern themes of sugoroku, the Harvard-Yenching Library also houses ten sugoroku boards published between 1933 and 1944 as part of its Manchukuo collection. Though created nearly a century after their late-Edo counterparts, these sugoroku continued to serve didactic functions: The game boards often feature recent military events, territorial expansion, notable military leaders, and/or exemplary behaviors deemed suitable for kids during the war.

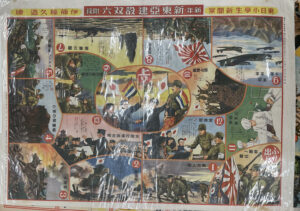

Image 10

Image 11

While one might expect a game to maintain its own set of rules and spatial dimensions distinct from the real world, some of these wartime sugoroku blur these boundaries between reality and play. For example, in Square 8, “A Landing Force” (rikusen tai 陸戦隊), of the “Construction of the New East Asia sugoroku” (Shin Tōa kensetsu sugoroku 新東亜建設双六, 1939, Image 10), players who roll a six are instructed to follow these instructions: “You died honorably. Please bow the direction of Yasukuni Shrine 靖国神社 and then continue.” (Image 11) This moment exemplifies how the spatial dimensions of the game extend beyond the confines of the board itself, as it is the players’ physical bodies—not merely their tokens—that are enlisted to perform ritualistic acts of reverence toward the military.

Image 12

Another example of similar blending the game and the real world is be found in the “Japan-China Incidents and Battlefields sugoroku” (Nisshi Jihen jinchū sugoroku : Keisuisen no maki日支事變陣中雙六: 京綏線之卷, 1937, Image 12). As players navigate the hand-drawn illustrations of major incidents and battles depicted in the central section of the board, they can refer to the periphery for corresponding photographs of the sites. This combination of illustrations and photographs offers players a layered perspective on the conquered territories, showcasing both natural landscapes and cultural landmarks, such as the Buddhist cave-temple site in Datong, Shanxi.

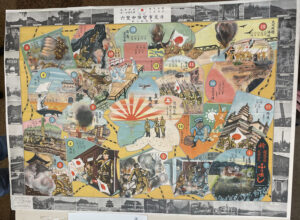

Image 13

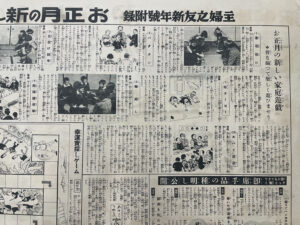

The majority of the WWII sugoroku boards were also published in the New Year season. For instance, the “China Incidents – Imperial Japanese Armed Forces’ Crushing Victory sugoroku” (Shina Jihen kōgun taishō sugoroku : Shufu no Tomo shinnengō furoku支那事變皇軍大勝双六, Image 13) was published as an appendix to a New Year issue of the journal Housewife’s Friend (shufu no tomo 主婦の友). On the backside of the game board is an introduction to trending and affordable New Year games for families during the war (Image 14), such as “(paper) frog derby” (kaeru dābī 蛙ダービー) and “exterminate the spies” (supai taiji スパイ退殺).

Image 14

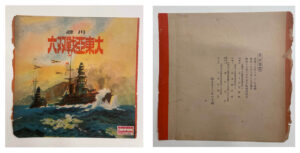

Image 15

Among these boards, only one, the “Great East Asia Battles sugoroku: senryū poems included” (dai Toa-sen sugoroku : senryū iri 大東亞戰双六 : 川柳入, 1942, Image 15), is preserved with its envelope (Image 16 & 17). A sticker attached to the lower right corner of the envelope reveals an interesting detail concerning censorship around this time: The sticker notes that the design was approved by the “Regulation Association of Japanese Toys and Dolls” (nihon gangu nigyō rui tōsei kyōkai 日本玩具人形類統制協会).[9]

Image 16 and Image 17

Despite their diverse themes and historical contexts, sugoroku board games in the HYL collection reveal the multifaceted ways in which games can mirror and shape societal ideologies and norms. Just as sugoroku games traditionally mark the start of a new year, we hope this article serves as a starting point for further exploration into this rich and intriguing body of cultural artifacts.

Footnotes and Acknowledgements:

The authors give thanks to Professor Eiko Kawamura for her help in this project.

[1] It should be noted that there was another kind of board game in Japan named ban-sugoroku 盤双六 (“board sugoroku”), a type of backgammon that was first introduced to Japan in the seventh century, enjoyed popularity during medieval times, and declined in the early modern era due to the influx of Western backgammon. See Masukawa Koichi, “Ban-sugoroku: Japan’s Game of Double Sixes,” in Colin Mackenzie and Irving Finkel ed., Asian Games: The Art of Contest (New York: Asia Society, 2004), 105.

[2] Other popular themes of the game include famous places (meisho 名所), merchandising, kabuki actors, and even ghosts and monsters.

[3] One copy of the corresponding game board is preserved in the Tokyo Metropolitan Library 東京都立図書館: Tokyo Metropolitan Library 東京都立図書館. Kenretsu teifu honchō misao sugoroku 賢烈貞婦本朝操寿古呂久. https://archive.library.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/da/detail?tilcod=0000000004-00000353.

[4] Please refer to the Tokyo Metropolitan Library 東京都立図書館 for the corresponding game board. https://archive.library.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/da/detail?tilcod=0000000004-00000351.

[5] Ryūtei Tanehiko’s 柳亭種彦 (1783-1842) Sukikaeshi 還魂紙料 (1826) nominates it as one of the potential origins of e-sugoroku. See Choochotkaew Saranya サランヤー シューショートケオ. “Kinsei nihon no yūgi ni okeru hotoke no hyōjō: bukkyōkei sugoroku wo chūshin ni shite 近世日本の遊戯における仏の表象: 仏教系双六を中心にして [“Buddha’s Representation in Japanese Edo-period Buddhist Sugoroku Games”],” Ōsaka daigaku gengo bunka kenkū ka nihongo bunka senmon hakase ronbun大阪大学言語文化研究科日本語日本文化専攻博士論文 (2017), 5-6.

[6] Scholars have identified other versions of the “Buddha Dharma sugoroku” that come with a dice, with the three disciplines and three poisons engraved on its sides. See Yamamoto Masakatsu 山本正勝, sugoroku yūbi 双六遊美 (Tokyo: Unsōdō 芸艸堂, 1988), 23.

[7] Based on the length and the missing part on the lower part of the printed border, we can tell that it’s printed by the same block of carvings as the Muryōjukoku-jōdo-sugoroku 無量寿国浄土双六 stored at the Tokyo Metropolitan Library and the Sōda Collection 宗田文庫at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. https://lapis.nichibun.ac.jp/sod/Detail?sid=11-4-19&eid=01.

[8] There is another type of e-sugoroku that is closely related to the Kumano nuns and their etoki storytelling practice. Transmitted within temples, these game boards were hung together with the Kanshin Jikkai Mandala for a ritual dedicated to Fudō Myōō. See Ogurisu Kenji 小栗栖健治, “Kumano-kei jōdo-sugoroku ron jōsetsu 熊野系「浄土双六」論序説,” Etoki kenkyū 絵解き研究, no. 20-21 (2007), 77-109.

[9] For more information on the regulation association, see Japan Toy Museum 日本玩具博物館, https://japan-toy-museum.org/archives/90.